Reconstructing the 2007-2008 Financial Crisis

Using X-Act® OBC Platform, we were able to reconstruct the global financial singularity of 2007 and 2008. Obviously the constructed solution came too late to spare the world from economic turmoil. It is not our intent to join the after-event agents of prophecy. Rather our goal is to use a scientific approach to reverse engineer what happened and in doing so prove the usefulness of mathematical emulation as a preventative solution.

Financial Dynamics in 2007

To analyze the root cause of the 2007-2008 financial crisis, we built a mathematical emulator that represented the financial market dynamics prior to the crash. This included the financial engines and dynamic flows among them and explicitly the dependencies on the internal structure and the external influencers that impact market performance.

In building the mathematical emulator, we put particular emphasis on the first category of direct dependencies (in couples: edges, vertices or a mix) as well as the indirect dependencies based on the fact that each and every part of the first category could be influenced by the impact on each category from the already-impacted participating components.

A perturbed structural model can be mathematically expressed in the form of participating inequalities. Each inequality contributes, through different amplitude and frequency, to the overall solution. Mathematically based solutions of this class are generally validated through three criteria:

- The solution should be representative to the process dynamics

- The solution should be accurate with respect to a real environment outcome with identical initial conditions

- The solution should allow a predictable precision that provides sufficient confidence in decision making and execution under different initial conditions

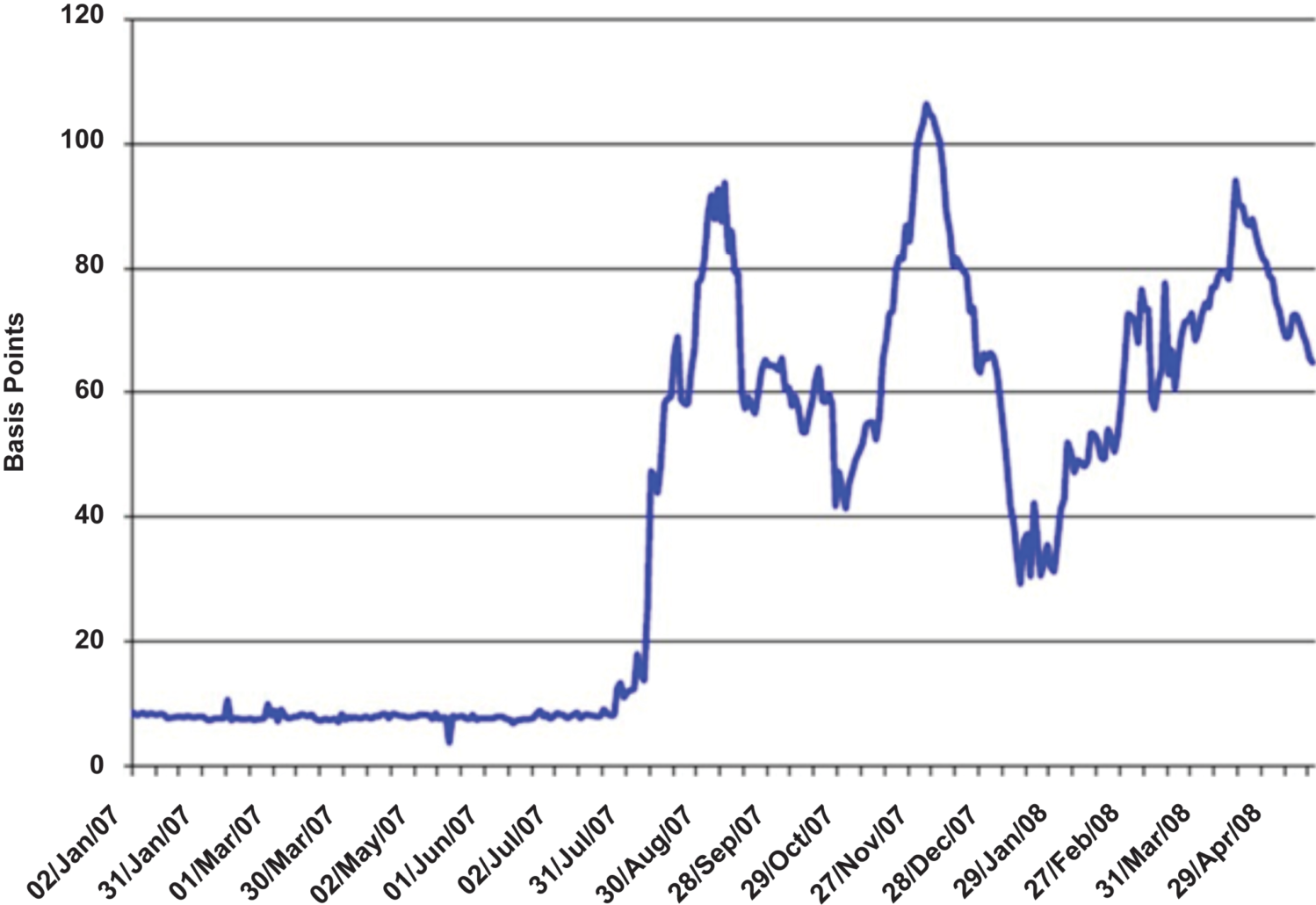

Mathematically speaking, we can consider that the coupled business dynamics-initial conditions will express and produce speeds, and the influencers will provoke accelerations. If we project these principles on the financial meltdown of 2007, we find that the system was stable (at least apparently) until the foreclosure rate went from 2 to 3 percent—the increase corresponding to more than 50% for subprime mortgages— and representing 10.5% of the US housing market (which was supposedly a low risk financial instrument). As is the case with mortgages, this amount was not distributed, but the full amount represented a direct loss to the financial institutions.

The Singularity is Precipitated by a Heating of the Market

The treasury secretary Paulson says, “The housing bubble was driven by a big increase in loans to less credit worthy, or subprime, borrowers that lifted homeownership rates to historic levels.” But this explanation alone is not sufficient to explain the collapse of the whole financial system based solely on foreclosure propagation.

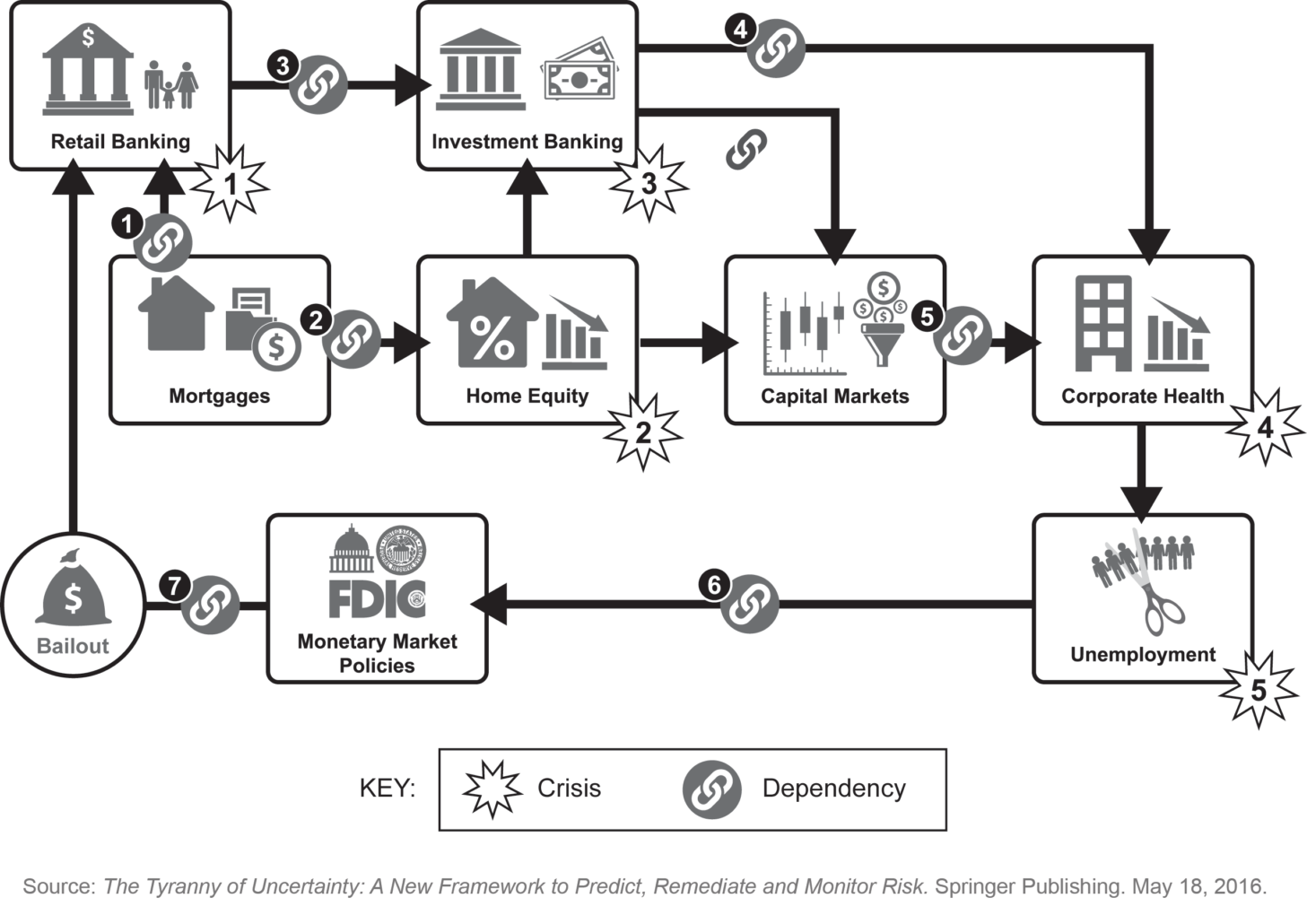

Our discovery of dynamic complexity through mathematical emulation allowed us to clearly point to the real cause: the market dynamics caused a singularity and dynamic complexity was the real cause of the crisis. This fact was not identifiable by the risk management and mitigation methods used pre-crisis. In short, the housing crisis was quickly overshadowed by a much bigger crisis caused by the dependencies of intertwined financial structures (connected through financial instruments, such as mortgage-backed securities) that by design, or by accumulation, caused the market collapse.

In other words, if someone wanted to design a system that would lead to a devastating crisis, the financial system of 2006 through 2008 was the perfect example of doing just that. If you use a similar structure with the level of dynamic complexity, you can replace housing with credit card as the predominant financial instrument, then back it up with securities (along the lines of mortgage-backed securities) and you will the same recipe for disaster.

Using X-Act® OBC Platform service we were able to model how the crisis was communicated from mortgage through home equity origination to contaminate the whole financial market in much larger amplitude than the variance in home mortgage interest rate over 20 years. Mortgage and housing market conditions create cycles of economic crises that repeat approximately every six years. However, the singularity that surprised even the U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman in 2007 held much deeper and wider causes for the collapse—namely the effects of dynamic complexity—than was the case in previous cycles.

The Singularity Hits When the System Becomes Out of Control

We used the causal emulation step of our methodology to measure the impact of the system contamination agent, which had been identified as mortgage-backed securities (MBS). After MBSs hit the financial markets, they were reshaped into a wide variety of financial instruments with varying levels of risk. This bundling of activities blurred the traceability of the original collateral assets. Interest-only derivatives divided the interest payments made on a mortgage among investors. When interest rates rose, the return was good. If rates fell and homeowners refinanced, then the security lost value. Other derivatives repaid investors at a fixed interest rate, so investors lost out when interest rates rose since they weren’t making any money from the increase. Subprime mortgage-backed securities were created from pools of loans made to subprime borrowers. These were even riskier investments, but they also offered higher dividends based on a higher interest rate to make the investment more attractive to investors.

In August 2008, one out of every 416 households in the United States had a new foreclosure filed against it. When borrowers stopped making payments on their mortgages, MBSs began to perform poorly. The average collateralized debt obligation (CDO) lost about half of its value between 2006 and 2008. And since the riskiest (and highest returning) CDOs were comprised of subprime mortgages, they became worthless when nationwide loan defaults began to increase. This would be the first domino to fall in the series that fell throughout the U.S. economy.

How the MBS’s brought Down the Economy

When the foreclosure rate began to increase late in 2006, it released more homes on the market. New home construction had already outpaced demand, and when a large number of foreclosures became available (representing up to 50% of the subprime mortgages) at deeply discounted prices, builders found that they couldn’t sell the homes they’d built. A homebuilder can’t afford to compete with foreclosures at 40 percent to 50 percent off their expected sales price. The presence of more homes on the market brought down housing prices. Some homeowners owed more than their homes were worth. Simply walking away from the houses they couldn’t afford became an increasingly attractive option, and foreclosures increased even more.

Had a situation like this taken place before the advent of mortgage-backed securities, a rise in mortgage defaults would nonetheless create a ripple effect on the national economy, but possibly without reaching a singularity. It was the presence of MBSs that created an even more pronounced effect on the U.S. economy and made escaping the singularity impossible.

Since MBSs were purchased and sold as investments, mortgage defaults impacted all dimensions of the financial system. The portfolios of huge investment banks with large and predominant MBSs positions found their net worth sink as the MBSs began to lose value. This was the case with Bear Stearns. The giant investment bank’s worth sank enough that competitor JPMorgan purchased it in March 2008 for $2 per share. Seven days before the buyout, Bear Stearns shares traded at $70[2].

Because MBSs were so prevalent in the market, it wasn’t immediately clear how widespread the damage from the subprime mortgage fallout would be. During 2008, a new write-down of billions of dollars on one institution or another’s balance sheet made headlines daily and weekly. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-chartered corporations that fund mortgages by guaranteeing them or purchasing them outright, sought help from the federal government in August 2008. Combined, the two institutions own about $3 trillion in mortgage investments[3]. Both are so entrenched in the U.S. economy that the federal government seized control of the corporations in September 2008 amid sliding values; Freddie Mac posted a $38 billion loss from July to August of 2008[4].

When Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac won’t lend money or purchase loans, direct lenders become less likely to lend money to consumers. If consumers can’t borrow money, they can’t spend it. When consumers can’t spend money, companies can’t sell products, and low sales means lessened value, and so the company’s stock price per share declines. So, on one side the capital market is tightening due to the MBSs and CDOs but also corporations suffer, as consumers lessened their consumption, and as money and credit tightened gradually. Businesses then trim costs by laying off workers, so unemployment increases and consumers spend even less. When enough companies (not only banks and other financial institutions but also corporations and finally investors) lose their values at once, the stock market crashes. A crash can lead to a recession. A bad enough crash can lead to a depression; in other words, an economy brought to its knees[5].

Preparing to Avoid the Next Financial Singularity

The predictive emulation shows us that an excessive integration of financial domains without understanding how dynamic complexity will be generated is the equivalent of creating a major hidden risk that will always surprise everyone involved. Either because the predictive tools can’t easily identify the role dynamic complexity plays, or due to imprudent constructs that seem to be acceptable options—if the world is flat and the dynamics are linear. These two assumptions are obviously wrong. Science teaches us the concept of determinism (all events, including human action, are ultimately determined by causes external to will).

Undoubtedly, financial markets will continue to pose grave risks to the welfare of the global economy as long as economic stakeholders are unable to accurately measure dynamic complexity or understand all the steps required to protect their assets. We must test and expand upon the presented universal risk management methods to define a better way forward that allows economic stakeholders to predict a potential singularity with sufficient time to act to avoid crisis of this magnitude in the future.